This is Part 4 of a blogged essay “Steampunk Data Science.” A table of contents is here.

Lafayette Mendel, Elmer McCollum’s post-doc mentor at Yale, was intrigued by his mentee’s foray into the chemistry of nutrition. Even if the results were puzzling, Mendel saw great potential in the controlled synthetic food experiments in rodents. Mendel recruited Thomas Osborne and Edna Ferry to synthesize dozens of diets for rats and compile their results in a two-volume monograph. They focused on providing the bare backbone macronutrients of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, but purified the food to be as basic as possible.

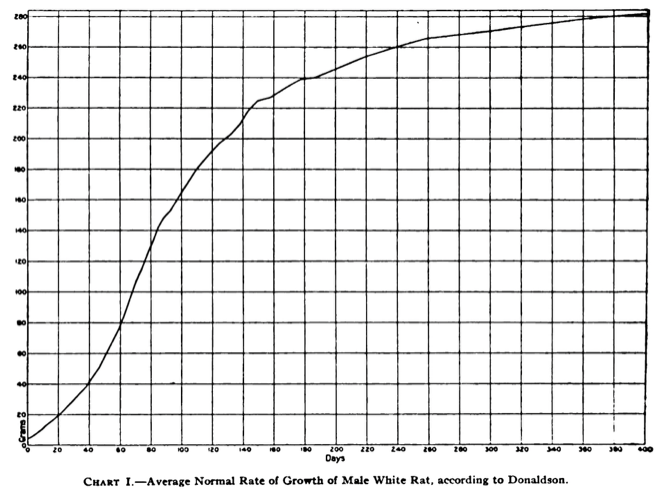

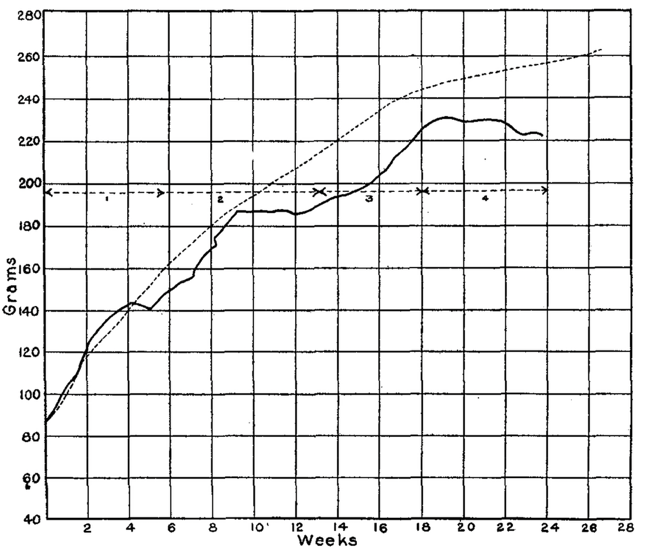

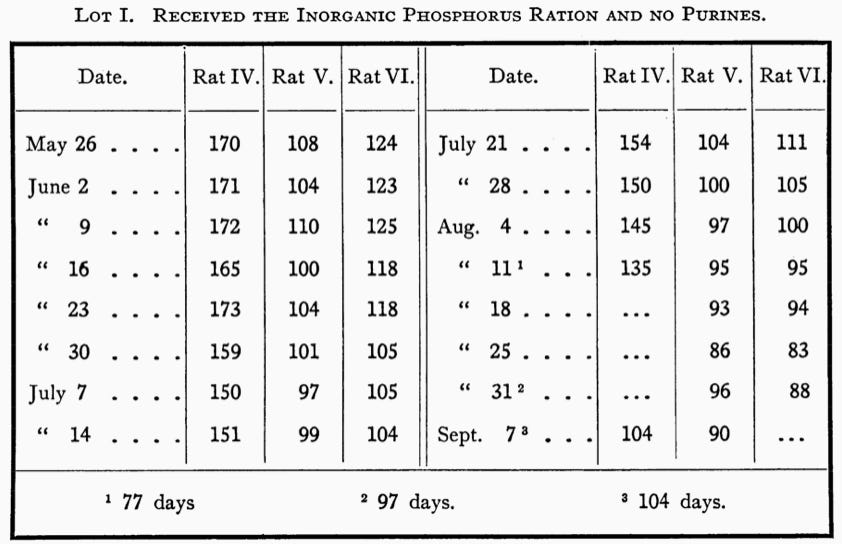

One of the Yale team’s key insights was comparing the relative value of diets by tracking rat growth against a baseline of “normal” growth. They drew on the rat studies of Henry Donaldson, Elizabeth Dunn, and John Watson, who used rats to understand the development of the nervous system. Donaldson et al. had weighed dozens of rats at different developmental stages and recorded the average and extreme weights of their samples. This is the average weight of Donaldson, Dunn, and Watson’s rats over time:

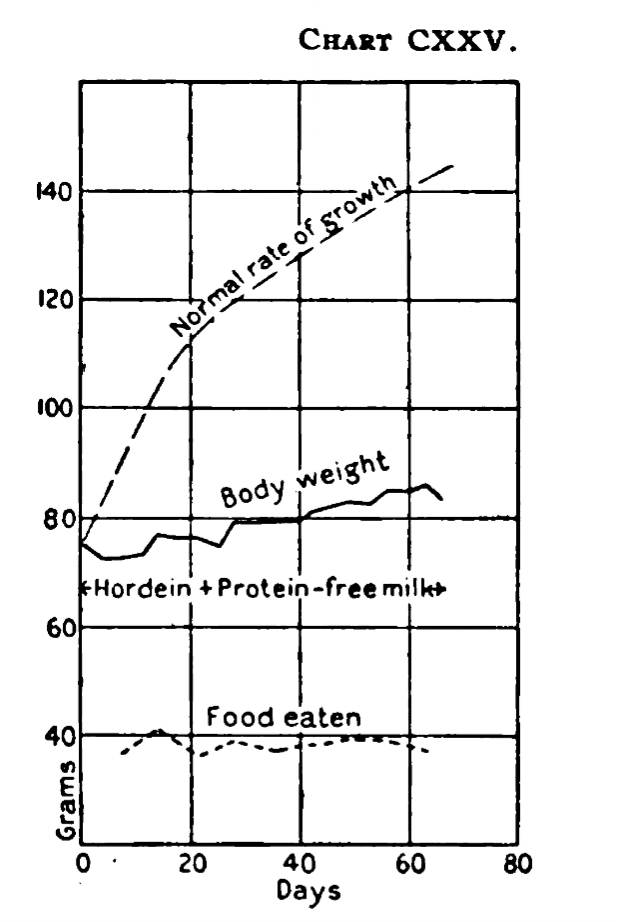

This normal growth curve eliminated the need for control groups when studying rat diets: a good diet would hit the curve, a bad diet would miss it. Osborne, Mendel, and Ferry first used it to disprove McCollum’s palatability hypothesis. They found a diet that the rats readily devoured but could not sustain normal growth. It consisted of hordein (a type of gluten), starch, agar, lard, and “protein-free milk.” Delicious. The milk was boiled and processed to remove fats and proteins, leaving behind milk sugars and other substances that were unknown at the time.

Even though the rats ate their fill of this mixture, their growth was terribly stunted.

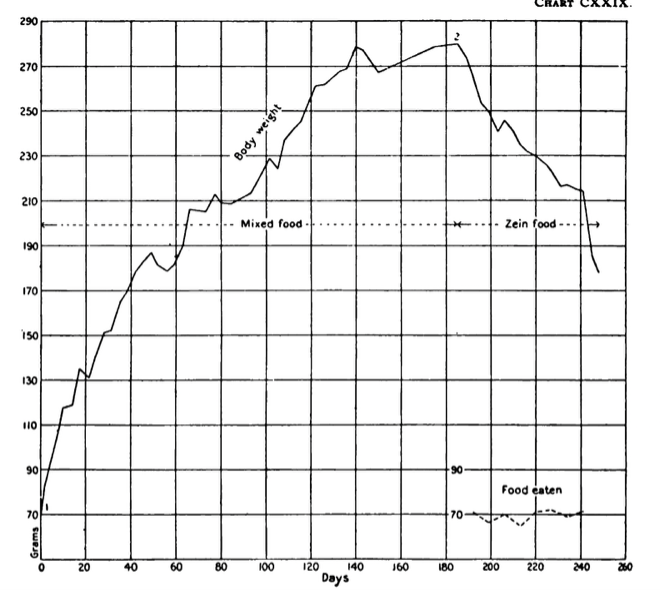

The Yale team plotted the growth of individual rats, rather than the averages of multiple rats. With such individualized studies, they could also demonstrate the effectiveness of dietary changes. Here is another prototypical paper from their research monograph.

The rat was fed multiple diets over its life. The experiment begins with a mixed food diet and then switches to a purified food. Soon after the dietary switch, the rat’s growth reverses, and it rapidly loses weight. Clearly, there is something deficient with the purified food. This sort of single-subject temporal experimentation let them hone in on which of the many food substances we eat are necessary for survival. What would we call this today? A “within-subject crossover design?” What’s the p-value? Whatever the case, other chemists and biologists were convinced there was something important going on in these studies, and the work won Osborne and Mendel a Science paper. They would be credited with the discovery of essential amino acids.

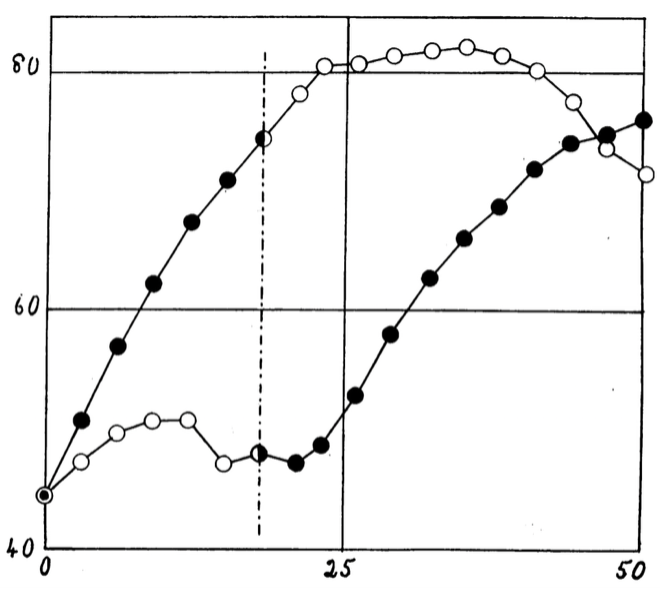

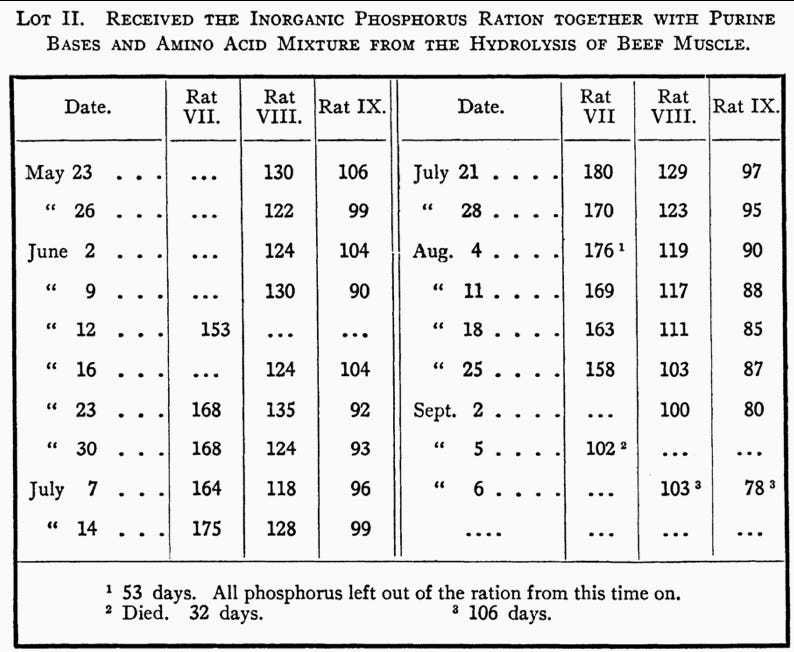

F. Gowland Hopkins, a nutrition researcher at Cambridge who had discovered the amino acid tryptophan, happened across their work in those illustrious pages and realized that he had already conducted similar experiments years earlier. Hopkins hadn’t written up his rat diet findings because he suffered an illness that had taken him out of the lab. Likely, he also hadn’t realized the significance of his findings until seeing Osborne and Mendel’s write-up. Wanting to join in on the party, Hopkins rushed to write up his earlier experiments and sent them to The Journal of Physiology. Figure 2 in that paper arguably won him the Nobel Prize.

In this experiment, there were two groups, each with eight rats. Each dot in the plot is the average weight of the group on a particular day (the x-axis is days, the y-axis is grams). The white dots correspond to rats fed only bread. The black dots correspond to rats fed bread and a tiny amount of milk. The rats with the milk supplement grew dramatically faster than those fed bread alone. Just like the Yale team, Hopkins had performed a crossover study. At day 18, he swaps the diets of the two groups. Subsequently, the milk-fed rats stopped growing on their milk-free diet. In sharp contrast, the rats fed bread only started to grow once Hopkins gave them some milk.

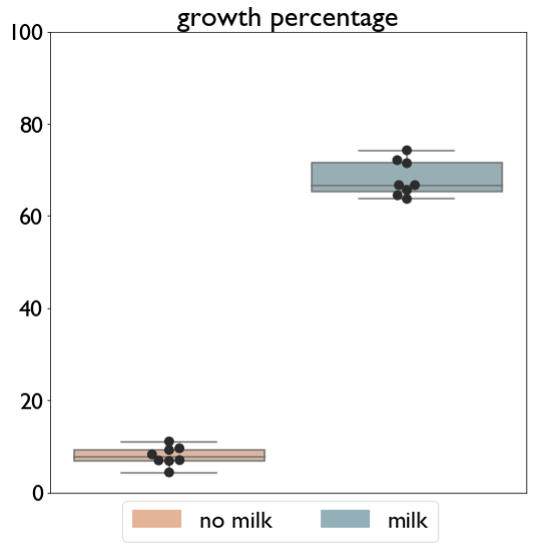

Hopkins’ paper includes a detailed appendix that shares much of the raw data plotted in the paper’s figures. For the plot above, he does not share the complete growth series for each rat, but he does list the rat weights at days 0, 18, and 50. Using the weights at days 0 and 18, I can create a more modern display of the data, revealing the variation within the groups rather than just representing the averages. In Figure 8, I plot the percentage growth from day zero for each rat, splitting them into the groups fed milk and those not fed milk.

Each dot here corresponds to the percentage growth of an individual rat. The shaded region corresponds to the middle half of the data. The line in the shaded region is the median of the data. The lines outside the box denote the extremes of the data. Without milk, all of the rats grew less than 20% over the 18 days. With milk, every rat grew more than 60%. Scientists didn’t need a hypothesis test to see that something incredible was in the milk.

Meanwhile, back in Madison, Elmer McCollum was stressed out. Not only was he confused by his early experiments, but he was embarrassed by the refutation of his work by Mendel’s team. He was distracted by the oppressive obligations of faculty life, found teaching an unwelcome burden, and resented being tasked with working on the cow experiment. Ah, the professor life. On top of all this, he would admit later that he was not naturally gifted at caring for his rats. The combination left his rat studies far less productive than he had hoped.

The missing catalyst arrived in 1909. Marguerite Davis had recently moved back to Madison to care for her father after the death of her mother. Davis had completed her bachelor’s degree at Berkeley and hoped to continue some form of graduate study while also looking after her dad. She told McCollum she’d be willing to do freelance research with him so she could learn biochemistry. McCollum agreed, and Davis began to learn the ways of the lab. Davis quickly noted that McCollum, though proficient at catching rats, was terrible at keeping them. His colony was struggling and in general disarray. She offered to care for them, and McCollum was overjoyed to pass off the rat-keeping responsibility. Davis not only enjoyed the work but also had a talent for running the experiments. Within a year, McCollum and Davis would publish revolutionary findings in the biochemical foundations of nutrition.

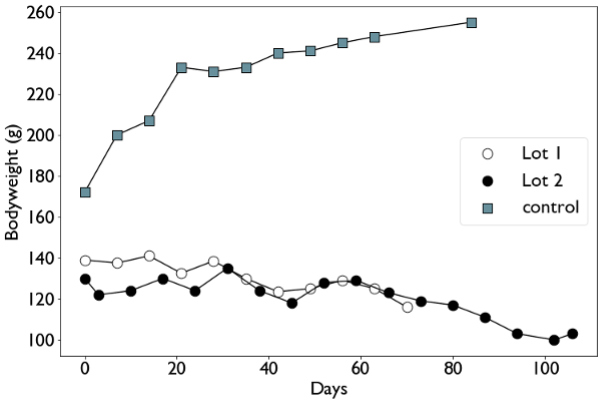

McCollum and Davis tried to figure out what exactly was missing from the protein-free milk of the Yale experiments. They devised a procedure to isolate the critical component by centrifuging egg yolks in an ether bath to separate a key fat-soluble material. They found that this isolated substance was itself sufficient to trigger rat growth.

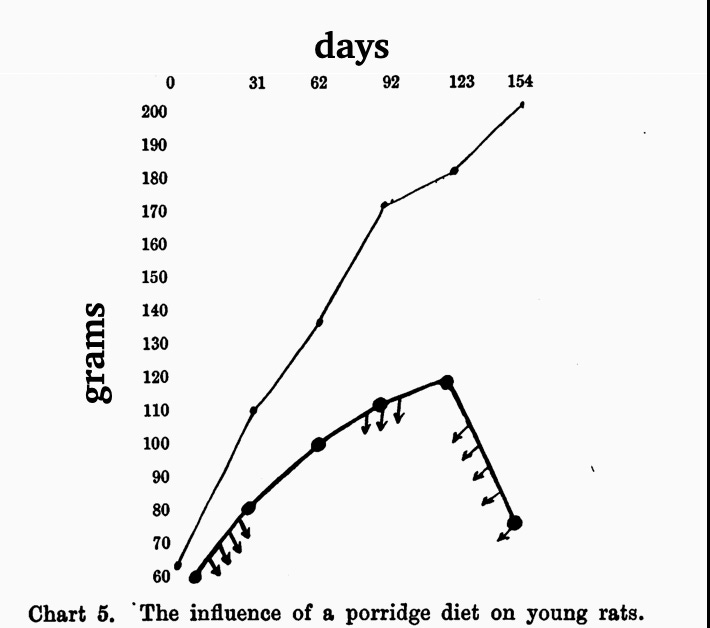

Here’s a typical example of their experimental results, which they presented in the same style as Mendel and collaborators.

For the first period, when the rat was young, McCollum and Davis fed the rat salt, protein, fats, and a little bit of carbohydrates. For the second period, they removed the fat. In this second period, the rat’s weight eventually plateaus. Then, in period three, they added the fat-soluble compounds from the egg yolk. Whatever this stuff was, it sufficed to reignite the rat’s growth.

They found this pattern remarkably repeatable. On the simple synthetic diets of only pure protein (casein), sugar (lactose), carbohydrates (starch and dextrine), and fats (lard), the rats displayed striking symptoms of malnourishment. They would languish and develop crusty buildup in their eyes. They wouldn’t mate. Adding the ether extract of egg yolk consistently cured the poor growth in these rats and fully restored them to normal.

McCollum and Davis considered five case studies of rats and their associated growth curves sufficient evidence of a major discovery. They wrote:

We have seen this prompt resumption of growth after a period of suspension result from the introduction of ether extract of butter or of egg in about thirty animals and are convinced that these extracts contain some organic complex without which the animals cannot make further increase in body weight, but may maintain themselves in a fairly good nutritive state for a prolonged period.

This fat-soluble compound turned out to be Vitamin A.

Subscribe now

By Ben Recht